- Home

- Soko Morinaga

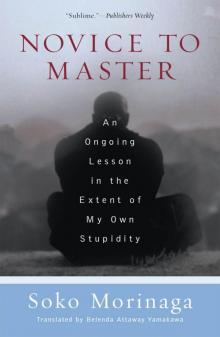

Novice to Master

Novice to Master Read online

everybody loves

novice to master!

“A real gem.”—Peter Alsop, Tricycle

Editor’s Choice. “The story of a man’s devotion to getting it— whatever it may be. It is a codex on the worth of such a pursuit.”

— The Review of Arts, Literature, Philosophy and the Humanities

“A moving story. Morinaga’s direct wisdom bubbles through the pages. Brilliant.”

—Tom Chetwynd, author of Zen and the Kingdom of Heaven

"Morinaga must be the Cal Ripken of Zendom. It’s a touching story of phenomenal growth, wisdom, and although he never owns up to it, enlightenment. A wondrous tale."

—NAPRA ReView

“Unpretentious, poignant and insightful.

Artfully written and translated.”

—Sumi Loundon, editor of Blue Jean Buddha

“Soko Morinaga has taken me places that maps can only hint of. This is one of the rarest books, among but a handful of such truly wondrous books—words on the order of Issa and Thoreau—the kind that changes your mind and your eyes for the rest of your days.”

—Bill Shields, author of The Southeast Asian Book of the Dead

“Should be particularly valuable to those who have not been previously acquainted with Japanese Zen.”

—Rapport

“A touching portrait of struggle and growth, evidence that the path to liberation is not a solitary one. We should all be so fortunate as to learn from the examples of idiocy in our own lives.”

—Paul W. Morris, editor of KillingTheBuddha.com

“I was touched by Morinaga’s stories of his own life. He speaks of his own experiences of loss and depression, and of working with others who are suffering and afraid. I feel him reaching out in compassion to me, the reader, concerning my own fear of dying, my fear of living. His modest and cheerful voice encourages me.”

—Susan Moon, editor of Turning Wheel and author of

The Life and Letters of Tofu Roshi

“Popular books on Zen Buddhism often dish out insights like McDonald’s serves up burgers. This humorous, autobiographical book is Zen for people who know you can’t get caviar at McDonald’s.”

— Psychology Today

Librarian’s Choice. “A truly inspiring book for those looking for spiritual meaning in life.”

—National Library Board of Singapore

“Inspiring, challenging and ultimately humbling.”

—Martine Batchelor, author of Meditation For Life

“With a fine sense of humor and commendable patience, Morinaga endures the rigors of training in a Zen monastery: sleepiness, a constant empty stomach, silence in the dining hall, and the strictness of the master. This combination memoir-and-wisdom-resource provides a lively and enlightening overview of Zen, and wonderful anecdotes on living in the present moment.”

—Spirituality and Health

“Anyone who reads this charming memoir can only wish they had the opportunity to meet this modest yet wise man. Written with gentle good humor that takes aim at his own failings without finding errors in others, the book serves up the most subtle form of enlightenment.”

—New York Resident

novice to master

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

© 2004 Belenda Attaway Yamakawa

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without the permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morinaga, Soko, 1925-

Novice to master : an ongoing lesson in the extent of my own stupidity / Soko Morinaga ; translated from the Japanese by Belenda Attaway Yamakawa—1st pbk. ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-86171-393-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Spiritual life--Zen Buddhism. 2. Zen Buddhism--Doctrines. I. Title.

BQ9288.M67 2004

294.3'444--dc22

2004000200

08 07 06 05 04

5 4 3 2 1

Cover by Laura Shaw Design

Interior design: Gopa & Ted2

Wisdom Publications’ books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for the permanence and durability set by the Council of Library Resources.

Printed in Canada

table of contents

Acknowledgments

Preface

Part I: novice

The Prospect of My Own Death

Nothing Is Certain

The Encounter at Misery’s End

There Is No Trash

Consumed with Cleaning

Confucius Gives Jan Yu a Scolding

Working It Out for Myself

“I Can’t Do It”

Between Teacher and Student

That’s Between Him and Me

Three Types of Students

“For the Disposal of Your Corpse”

The Meaning of Courage

What Am I Doing Here?

Living Out Belief in Infinite Power

Part II: training

A Heart That Does Not Move

Getting to Know My Own Idiocy

Routine in the Monastery

No End to Practice

Part III: master

What’s It All About?

God Is Right Here

Is Death Something We Cannot Know?

We Are Like Water

The Death of My Grandfather

Inexhaustible Dharma

To Die While Alive

Give Yourself to Death

Buddha Life

About the Author

About the Translator

acknowledgments

WARM THANKS to my sister, Carolyn Attaway O’Kelly. To Professor Minoru Tada of Otani University. To Josh Bartok at Wisdom Publications.

Morinaga Roshi offered practical advice at a time when I most needed it. I try to follow, with varying degrees of success, his wise council on matters of practice within daily life. The main thing he urged me to do: translate. Thank you, Roshi.

Belenda Attaway Yamakawa

preface

A WHILE AGO I gave a public lecture at a university. The speaker who preceded me talked for about an hour and a half, running over his allotted time. The break period between our talks was shortened, and I was called to the podium right away. Concerned for the audience, I opened by asking, “Did you all have time to urinate?”

Apparently this was not what the audience had expected to hear. Perhaps they were particularly surprised because the person standing before them, talking about pissing, was a monk. Everyone broke into hearty laughter.

Having started out on this note, I continued to press on. “Pissing is something that no one else can do for you. Only you can piss for yourself.” This really broke them up, and they laughed even harder.

But you must realize that to say, “You have to piss for yourself; nobody else can piss for you” is to make an utterly serious statement.

Long ago in China, there was a monk called Ken. During his training years, he practiced in the monastery of Ta-hui, but despite his prodigious efforts, he had not attained enlightenment. One day Ken’s master ordered him to carry a letter to the far-off land of Ch’ang-sha. This journey, roundtrip, could easily take half a year. The monk Ken thought, “I don’t have forever to stay in this hall practicing! Who’s got time to go on an errand like this?” He consulted one of his seniors, the monk Genjoza, about the matter.

Genjoza laughed when he heard Ke

n’s predicament. “Even while traveling you can still practice Zen! In fact, I’ll come along with you,”—and before long the two monks set out on their journey.

Then one day while the two were traveling, the younger monk suddenly broke into tears. “I have been practicing for many years, and I still haven’t been able to attain anything. Now, here I am roaming around the country on this trip; there’s no way I am going to attain enlightenment this way,” Ken lamented.

When he heard this, Genjoza, thrusting all his strength into his words, put himself at the junior monk’s disposal: “I will take care of anything that I can take care of for you on this trip,” he said. “But there are just five things that I cannot do in your place.

“I can’t wear clothes for you. I can’t eat for you. I can’t shit for you. I can’t piss for you. And I can’t carry your body around and live your life for you.”

It is said that upon hearing these words, the monk Ken suddenly awakened from his deluded dream and attained a great enlightenment, a great satori.

I hope that as you read this, you will realize that I am not just talking about myself or about something that happened elsewhere. No, it is about your own urgent problems that I speak.

part one:

NOVICE

the prospect of my own death

IF I WERE TO SUM UP the past forty years of my life, the time since I became a monk, I would have to say that it has been an ongoing lesson in the extent of my own stupidity. When I speak of my stupidity, I do not refer to something that is innate, but rather to the false impressions that I have cleverly stockpiled, layer upon layer, in my imagination.

Whenever I travel to foreign countries to speak, I am invariably asked to focus on one central issue: Just what is satori, just what is enlightenment? This thing called satori, however, is a state that one can understand only through experience. It cannot be explained or grasped through words alone.

By way of example, there is a proverb that says, “To have a child is to know the heart of a parent.” Regardless of how a parent may demonstrate the parental mind to a child, that child cannot completely understand it. Only when children become parents themselves do they fully know the heart of a parent. Such an understanding can be likened to enlightenment, although enlightenment is far deeper still.

Because no words can truly convey the experience of enlightenment, in this book I will instead focus on the essentials of Zen training, on my own path to awakening.

Let me start by saying that Zen training is not a matter of memorizing the wonderful words found in the sutras and in the records of ancient teachers. Rather, these words must serve as an impetus to crush the false notions of one’s imagination. The purpose of practice is not to increase knowledge but to scrape the scales off the eyes, to pull the plugs out of the ears.

Through practice one comes to see reality. And although it is said that no medicine can cure folly, whatever prompts one to realize “I was a fool” is, in fact, just such a medicine.

It is also said that good medicine is bitter to the taste, and, sadly enough, the medicine that makes people aware of their own foolishness is certainly acrid. The realization that one has been stupid seems always to be accompanied by trials and tribulations, by setbacks and sorrows. I spent the first half of my own life writhing under the effects of this bitter medicine.

I was born in the town of Uozu in Toyama Prefecture, in central Japan. The fierce heat of World War II found me studying with the faculty of literature in Toyama High School, under Japan’s old system of education. High school students had been granted formal reprieve from military duty until after graduation from university. When the war escalated, however, the order came down that students of letters were to depart for the front. Presumably, students of science would go on to pursue courses of study in medicine or the natural sciences and thereby provide constructive cooperation in the war effort; students of literature, on the other hand, would merely read books, design arguments, and generally agitate the national spirit.

At any rate, we literature students, who came to be treated as nonstudents, had to take the physical examination for conscription at age twenty and then were marched, with no exceptions, into the armed forces. What is more, the draft age was lowered by one year, and as if under hot pursuit I was jerked unceremoniously into the army at the age of nineteen.

Of course we all know that we will die sooner or later. Death may come tomorrow, or it may come twenty or thirty years hence. Only our ignorance of just how far down the road death awaits affords us some peace of mind, enables us to go on with our lives. But upon passing the physical examination and waiting for a draft notice that could come any day, I found the prospect of my own death suddenly thrust before my eyes. I felt as though I were moving through a void day by day. Awake and in my sleep, I rehearsed the various ways in which I might die on the battlefield. But even though I found myself in a tumult of thoughts about death, there was no time for me to investigate the matter philosophically or to engage in any religious practice.

People who entered the army in those days rushed in headlong, fervently believing that ours was a just war, a war of such significance that they could sacrifice their lives without regret. Setting out in this spirit, we were armed with a provisional solution to the problem of death—or at least it was so in my case.

Among human beings, there are those who exploit and those who are exploited. The same holds true for relations among nations and among races. Throughout history, the economically developed countries have held dominion over the underdeveloped nations. Now, at last, Japan was rising to liberate herself from the chains of exploitation! This was a righteous fight, a meaningful fight! How could we begrudge our country this one small life, even if that life be smashed to bits? Such reckless rationalization allowed us to shut off our minds.

And so it was that we students set out in planes, armed only with the certainty of death and fuel for a one-way trip, with favorite works of philosophy or maybe a book about Buddha’s Pure Land beside the control stick, certain to remain unread. Many lunged headlong at enemy ships; still many others were felled by the crest of a wave or knocked from the air before making that lunge.

Then, on August 15, 1945, came Japan’s unconditional surrender. The war that everyone had been led to believe was so right, so just, the war for which we might gladly lay down our one life, was instead revealed overnight as a war of aggression, a war of evil—and those responsible for it were to be executed.

nothing is certain

FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE, I returned from the army alive. Over a shortwave radio, an item extremely hard to come by in those days, I listened to the fate of the German leaders who had surrendered just a step ahead of the Japanese. When I heard the sentence that was read aloud at the Nuremberg Trials, “Death by hanging,” the one word—hanging—lodged itself so tenaciously in my ears that I can still hear its echo. And then (perhaps through an American Occupation Forces policy?), a news film was shown. I saw this film at what is now the site of a department store, on the fifth floor of a crumbling cement block building that had only just narrowly escaped demolition in war-ravaged downtown Toyama.

In one scene, a German general was dragged to the top of a high platform and hanged before a great crowd that had assembled in the plaza. In another scene, the Italian leader Mussolini was lynched by a mob and then strung upside down on a wire beside the body of his lover. The film went on to show us how the dead bodies were subsequently dragged through the streets while the people hurled verbal abuse and flung rocks at them.

Wearing cast-off military uniforms, my classmates and I went back to school, one by one. We returned, young men unable to believe in anything and hounded by the question of right and wrong. Technically classes were resumed, but in reality no studying took place. If a teacher walked into the classroom, textbook under his arm, he would be asked to take a seat on the sidelines while members of the group who had just returned from the army took turns at the podium:

>

“Fortunately or not, we’ve been repatriated, and we’re able to come back to school. But what we thought to be ‘right,’ turned out overnight to be ‘wrong.’ We may live another forty or fifty years, but are we ever going to be able to believe in anything again—in a ‘right’ that can’t be altered, in a ‘wrong’ that isn’t going to change on us? If we don’t resolve this for ourselves, no amount of study is ever going to help us build conviction in anything. Well, what do you fellows think?”

This went on day after day.

It so happened that in those days we had a philosophy teacher named Tasuku Hara. He later went on to become a professor in the philosophy department at Tokyo University. He was an excellent teacher, and I was sorry to hear that he died quite young. Anyway, one day this Professor Hara, who was like an older brother to us, stood up and insisted that we let him get a word in.

Taking the rostrum, he proceeded to talk to us, “Kant, the German philosopher in whose study I specialized, said this: We humans can spend our whole lives pondering the meaning of ‘good’ and ‘evil,’ but we will never be able to figure it out. The only thing that human beings can do is come up with a yardstick by which to measure good and evil.”

Novice to Master

Novice to Master